Mind the Gap

Getting women's voices into policymaking

Foreword

The Rt. Hon Baroness Beverley Hughes

Having served previously as an elected representative in local

and national government, the Rt. Hon Baroness Beverley Hughes is now Deputy Mayor for Greater Manchester (Police, Crime, Criminal Justice and Fire).

I am delighted to introduce this publication which looks at how women can be better represented and involved in policymaking, and why this is so important.

It forms part of a wider University of Manchester initiative that has brought women from a range of backgrounds together to explore this critically important issue. It comes at a time of great opportunity and change when Greater Manchester is developing new models of governance as the result of the devolution of powers from central government to the city region.

Tackling inequality and enabling every person to fulfil her or his potential are key tenets of progressive politics that have been central to my own personal experience and political journey. Born in 1950, I came from a large family. My parents had no choice but to leave school at 14 and go into unskilled jobs, but they wanted more for their children. It was their relentless hard work, their aspiration for us and the introduction of the welfare state that together gave us, and thousands of other working-class children, access to the kind of education that is a springboard to social and economic advancement. This social mobility enabled us to stand on the shoulders of our parents.

I had expected that politics would continue to bring about and indeed increase these kinds of opportunities. But not only has social mobility stalled; the deep inequalities in our society persist. Women and girls, despite some undoubted improvements over the last fifty years or so, continue to be underrepresented in many of the important areas of life, to have less access to some key resources, and to experience more barriers to advancement than men.

In Greater Manchester, fewer women than men are in work, they are twice as likely to work part-time, and on average, they earn considerably lower rates of pay. Pregnancy is still a factor forcing women to leave their jobs. When women are in work or in apprenticeships, they are much less likely to be in well-paid sectors such as science and technology and much more likely to be in lower-paid sectors such as health and social care. Unpaid care is still predominantly the preserve of women and the biggest pay gap is for mothers. Almost a quarter of women aged 50-64 are caring for another adult, and certain types of serious crime - domestic violence, rape, sexual assault, stalking - differentially affect women.

It is therefore crucial that the opportunity of a new form of governance – through devolution – seeks, as a priority, to tackle gender inequality. Indeed, the overarching objective of devolution to enhance the city region’s social and economic wellbeing, arguably cannot be achieved unless the consequences of gender inequality are addressed as a core plank of policy.

For women, the starting point must be a critical mass of women within the political and executive leadership across Greater Manchester. This really matters. Having sufficient numbers of women - in all their diversity - around the decision-making table, is an absolute necessity if the views and experience of women are to inform policy.

At the time of writing, only two of Greater Manchester’s ten local authority leaders are women. Five of the ten chief executives are women but the chief officers of the key public services - police, fire, health, transport - are all men. We cannot wait for the slow progress of selecting leaders or appointing women to the most senior positions, before we press the case for women’s participation in policymaking and implementation.

We must think seriously about the barriers to women’s participation and remove them; establish ways for diverse women’s voices to be heard routinely and scrutinise all policy to ensure it has taken account of women’s views and experiences and considered the gender dimension.

The insights of the contributors here will help to drive forward this vital work in Greater Manchester and beyond, as we establish a strong foundation upon which our priorities for ‘turbo-charging’ women’s and girls’ equality can flourish.

Introduction

Francesca Gains, Leah Culhane, Temidayo Eseonu and Anna Sanders

Getting women’s voices into policymaking matters. For far too long there has been a clear gender inequality in the way we determine public policy; one that should no longer apply in modern times. How to gather evidence about inequalities, what techniques and tools will help redress the imbalance and the need for practical guidance for policymakers is what led to this publication.

The authors, a mix of academics, local and national campaigners and policymakers, first came together when they attended a ‘Getting Women’s Voices into Policymaking’ workshop held at The University of Manchester as part of the Economic and Social Research Council 2019 Festival of Social Science. Here, academics described evidence-gathering methods, campaigners involved in GM4women2028 and other campaign groups shared their experience of drawing women into policy discussions, while policymakers from the Greater Manchester Combined Authority Women’s Voices Task Group spoke about the practical realities of the policymaking process.

The workshop enabled the sharing of so many great ideas, experiences and energy for what could be achieved, that there was a determination to try to ‘capture and bottle’ it, and extend the conversation

more broadly.

In the pages that follow, our contributors share knowledge and experience on:

- How equalities evidence makes a real difference in policymaking around violence against women and girls

- The gaps on gender data worldwide and the need to address this

- Evidence of gender differences in the chairing and evidence-giving at parliamentary select committees and the Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s scrutiny panels

- Polling data on women’s voting – what it tells us, and what we know

- Citizen science techniques and how these can improve information and expertise in policymaking

- Listening exercises that help determine the experiences and diversity of women’s lives

- How creative techniques can unlock opportunities for expression

- Getting the diversity of women’s voices heard through inclusive co-production

- Citizens’ assemblies: what they offer, including policy deliberation on sometimes contentious policy choices

- How a policy machinery has been developed in Bristol to feed women’s voices from across the city into policymaking

- Equality impact assessments and how women’s budgeting adds to policy analysis

- How the Greater Manchester Combined Authority is developing an equalities strategy through the Women’s Voices Task Group

Finally, we close this publication with Chair of the New Local Government Network, Donna Hall CBE, who reflects on her experience of working in Greater Manchester and her hope to see more equality in policymaking.

We hope these contributions will encourage everyone involved in developing policy to gather information about women’s experiences and make use of the many different methods that are available. And, with a growing devolution agenda in England and Wales, we hope these insights and reflections will be taken up more widely to help ensure gender equality in policymaking, wherever it takes place.

The Equalities Equation and Violence Against Women: How women's voices + evidence = action

Francesca Gains

Progress towards achieving equality in life chances, so that all citizens can fulfil their potential, has been slow. Despite women having the vote for over 100 years and protection from equalities legislation since the 1970s, there are still significant inequalities in the educational, employment, care and retirement choices available to men and women. This national picture is replicated regionally, for example in Greater Manchester as The University of Manchester’s On Gender publication showed. With a growing devolution agenda in England and Wales, there is an urgent need to consider how devolved combined authorities can address gender, and other inequalities when developing public policy.

Of course, there has been gradual progress and improvements both in the diversity of our politicians and policymakers, and in the actions taken to tackle inequality. However, not enough is known about the impact of having more women in policy-making roles, or what policy actions might help to address gender inequalities. Research I conducted (with Vivien Lowndes of the University of Birmingham) examined if gender affected how police and crime commissioners (PCCs) prioritised the problem of violence against women and girls (VAW).

Firstly, we found that female PCCs were twice as likely to make VAW a priority - showing that having a diversity of policymakers brings different experiences and concerns forward. This is not to argue only women can speak out for other women; many male PCCs also recognised and prioritised this policy problem for action. However, it shows that increasing the number of women policymakers increases the likelihood of problems predominantly affecting women being recognised and acted on.

The role of equalities duties

But a second factor that made an even bigger difference was when PCCs (both men and women) took their equalities duties seriously, with those who demonstrated a serious commitment being nearly two and a half times more likely to prioritise this issue for action. All public officials have equalities duties since the 2011 Equalities Act and should ‘play their part in making society fairer by tackling discrimination and providing equality of opportunity for all’.

Our research showed that the PCCs who fully exploited the provisions of the duty asked for data about the incidence, the reporting and the prosecutions of different types of crime, and looked at the likelihood of victimhood broken down by gender. They sought other forms of evidence by talking to victims and campaign groups around issues such as violent crime. They publicised that evidence and worked with partners, the police and the public to develop policy proposals. Getting women’s voices into policymaking through gathering the evidence base and getting proposals into the policy process were all critical in getting action to improve gender equality.

Challenges and the path to the ‘equality equation’

Getting the ‘equality equation’ underway is not always straightforward. The evidence base isn’t always readily available, and some voices may not be sought out or listened to. There may not be the expertise and familiarity in how to gather the evidence needed and use it to inform action. And even when there is agreement about the need to address inequalities, there are challenges faced in getting change into policy action: the policy and political cycles sometimes work to different timescales and developing policy proposals requires policymakers to build coalitions of support and harness the resources to deliver change. This may be challenging, especially in local government at a time of austerity when resources have faced significant budgetary restraints.

The desire to share methods and experiences of what works in gathering evidence - which can then be used to feed into policymaking - is what the contributors to this publication hope to achieve.

For, as the example of the PCCs shows, where the equalities equation of women’s voices + evidence is used by policymakers, policy action is more likely to result.

Counting women, so women count

Jackie Carter

In the 1911 census, prior to women having the vote, suffragists and suffragettes were urged to boycott the census using the slogan: ‘if they do not count, neither shall they be counted’. Jill Liddington, a social historian, wrote about this in her book, Vanishing for the Vote. It is a fascinating read. She describes, through close analysis of historical records, how women reacted to this call to arms. But to what extent have women’s voices and experiences remained ‘hidden’, even today?

Early campaigners

Back in 1911 some did indeed hide, so as not to be counted, in protest against their lack of voting rights and the patriarchal question design on the census form. They actively denied their existence.

Others were determined to be counted, including Emily Wilding Davison who hid in a cupboard in the Houses of Parliament, so that her address could be recorded as Westminster. The National Archives holds the original census form in which we can see that this indeed was her recorded address on the night of the census.

Those committed female campaigners who stood up to be counted opted to do so to enable the government to gather accurate information for the purpose of health and welfare reforms.

Counting women: policy implications

If women are not counted, how can policy be developed to support them, those who rely on them, and the causes that affect women disproportionately?

Professor Diane Coyle has written extensively on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and how this is still the predominant measure modern societies use as a yardstick for progress. The measure excludes unpaid work. She points out that while there are difficulties in measuring unpaid work, the brunt of which predominantly falls on women, it is a challenge to measure all the data that we use to estimate GDP. Moreover, understanding that GDP is itself an estimate, with inherent uncertainty, is something else that needs to be considered and understood. Data about unpaid work are not collected systematically, with the consequence that policies do not take this into account.

Organisations like management consulting firm McKinsey & Co have produced figures for how much unpaid labour could add to the international economy, were it counted. In a 2019 report they consider gender parity in a broader sense, showing how correcting for this could positively affect the UK economy. The point here is that women, and work undertaken by women, needs to be measured and counted if policy debates are going to reflect the population, more than 50% of which is female. Time use surveys, for example, could be used to collect information on how women spend time in unpaid work. Their use is on the rise, but more data is needed.

Women are not a minority, and yet the debate about policies that affect predominantly women continues. In Caroline Criado Perez’s book, Invisible Women, she asks why aspects of UK policy are so unjust, then says: ‘The answer is simple: they aren’t looking at the data.’

Mind the (gender data) gap

The United Nation’s seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have one goal devoted exclusively to gender. Goal five, which seeks to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, recognises that too few countries either collect data on issues that matter to women, or do not have data that can be disaggregated to develop inclusive policies. Of course, it is not just about gender, and we need to look at these issues through an intersectional lens, with race, class, disabilities, poverty and so on. However, shining a spotlight on gender data gaps is a good start.

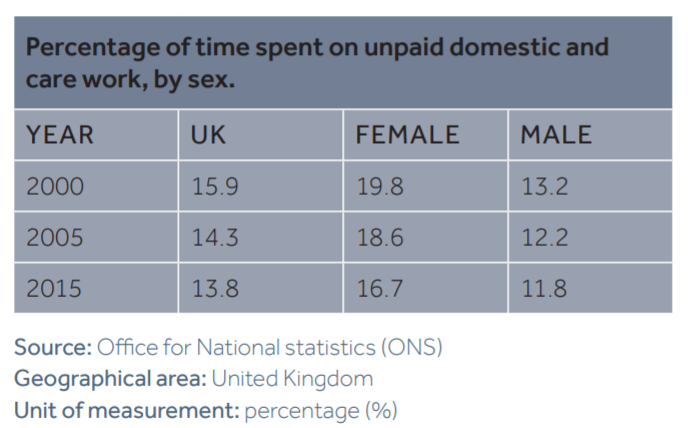

The UK Office for National Statistics has a site dedicated to showing the progress of data collection against all 17 of the SDGs. On first inspection, it looks like the data are available for all the targets and indicators that feed Goal five. However, if we take a look at 5.4.1 ‘Time spent on unpaid domestic work’ and inspect data points that inform this, disaggregated by sex, we find there is a difference: women spend more time on unpaid domestic work than men, and there are only three data points for this in 15 years. Once again, this confirms the need for more data.

The Data2X initiative set up by Hillary Clinton and Melinda Gates, was aimed specifically at closing the gender data gap internationally. The focus for this site is on global development statistics, but it indicates just how seriously the issue of gender data gaps is being taken across the world and how women, and the full nature of their roles, need to be counted.

A critical issue

Collecting data about women remains an issue today and is critical in order to be able to create policies that are inclusive, and that reflect women’s lives.

Evidence-informed policymaking can be powerful, but the evidence needs to include data that reflects all of society, not just a section of it. The gender data gap is finally getting some increasing attention and that can only be a good thing, but it is long overdue.

Women, and the full nature of their roles, must be counted to ensure policies that count, for everyone.

Footnote: Data are only available for the years 2000, 2005 and 2015, which are the years used on the X axis. Data were recorded between the periods June 2000 to September 2001, February 2005 to November 2005 and April 2014 to November 2015 respectively.

Case study

The gender balance of local and national scrutiny committees

Rachel Cooper

This case study profiles research looking at gender gaps in political representation undertaken by Rachel Cooper while on a University of Manchester Q-Step Centre placement with Professor Francesca Gains and Professor Anna Scaife.

Research aims

The purpose of this research was to discover if there are differences in the gender representation of central and local government committees. We aimed to find out the gender of the chairs of the scrutiny/select committees, as well as the gender breakdown of the elected representatives and those invited to give evidence.

Method

The time frame was April 2018-March 2019 for Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) and October 2018-July 2019 for Westminster, to fall in line with council and parliamentary sittings.

The following committees were chosen for comparison:

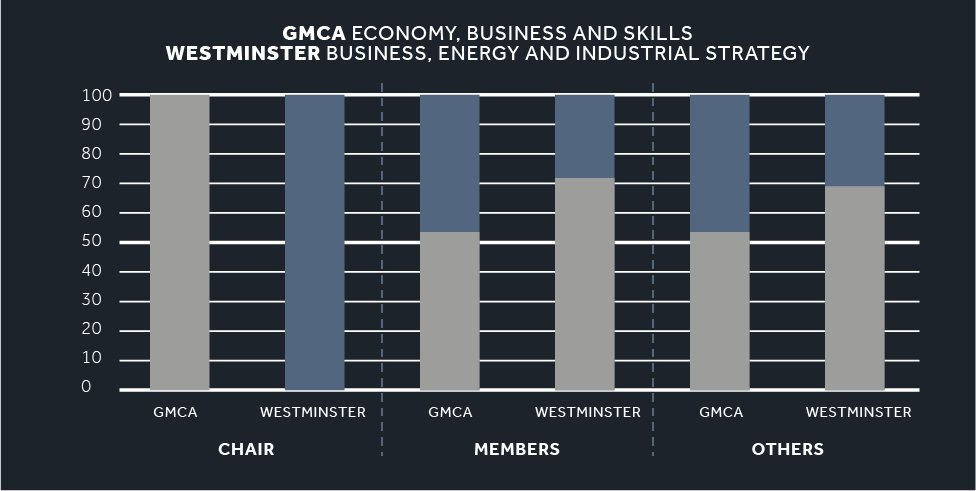

- GMCA’s Economy, Business Growth and Skills Committee with Westminster’s Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee

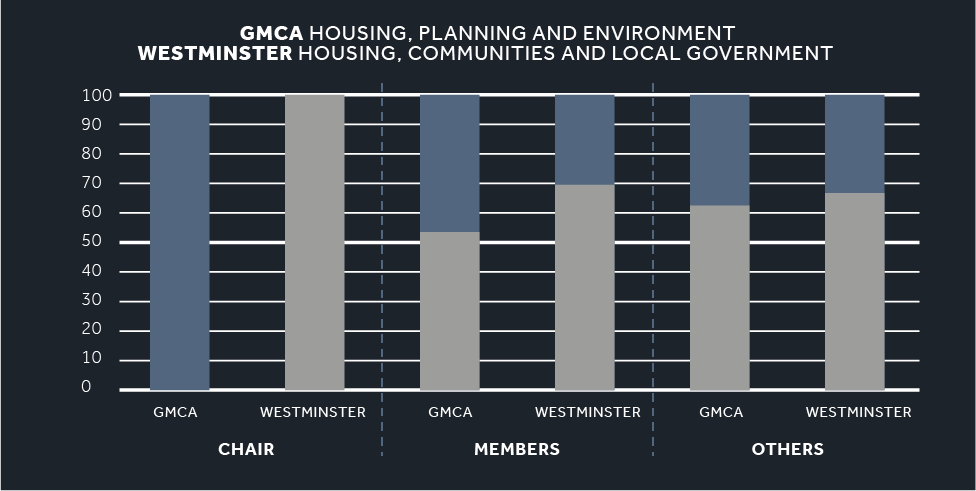

- GMCA’s Housing, Planning and Environment Committee with Westminster’s Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee

- GMCA’s Transport Committee, which included the Capital Projects and Policy Sub-Committee, Bus and TfGM Services Sub-Committee and the Metrolink and Rail Networks Sub-Committee, with Westminster’s Transport Select Committee

Several tools helped us with the data. For most of the data collection, a script using Python programming was used. PDFs for each meeting in the time frame were scraped and downloaded from their respective websites and converted into text files.

Code was then written to find the names within the text, using mainly the platform NLTK (natural language toolkit) among other Python packages.

The gender of those names was then determined using the Genderize package. Excel was used to clean the data and for the further analysis, calculating the percentages of males and females for each category.

The gender balance: results and conclusions

As the three graphs show, overall GMCA was more gender balanced than Westminster - particularly the Economy, Business Growth and Skills Committee,

which has a near equal gender balance for both committee members and 'others’ (for example experts giving evidence).

The least gender balanced of the committees were Transport - with both GMCA and Westminster having an 80/20 ‘balance’ in their members, as well as poor gender representation of the others present/giving evidence. Particularly interesting is the gender balance in Westminster’s Transport Committee, despite having a female chair. However, caution does need to be taken with the GMCA results, as (unlike the Westminster minutes) it is not entirely clear who is speaking. It may be the case that more women are invited, but whether they have a voice in that room is unknown. This is why they are referred to as ‘others’, because it is not clear what their role is in the meeting.

This research shows that data can be collected to bring insight into gender imbalance within politics.

More needs to be done to build up a detailed picture which can inform policies to tackle the lack of women’s voices and build greater equality in public debate and decision making.

Sources

Minutes of meetings available at:

www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/

https://democracy.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/mgListCommittees.aspx?bcr=1

Gender of names determined by Python Package www.genderize.io

Using polling data to capture women's voices

Anna Sanders

Women’s votes can play a crucial role in the outcome of elections. Women make up the majority of voters, comprising 54% of the British electorate. This is, in part, due to women’s greater longevity: of those aged 65 and over, 55% are women. But are policymakers sufficiently aware of the difference gender makes?

Traditionally, research has suggested that in the UK women have been more likely than men to vote Conservative, whereas men have been more likely to support Labour. Over time, however, this gender gap has narrowed to the point where, in recent elections, women have been slightly more likely than men to vote Labour and less likely to vote Conservative. This pattern in vote choice is broadly similar to that observed in other countries across western Europe.

Although there are relatively small gender differences in vote choice at the aggregate level, there are some areas where women and men differ more specifically, ranging from the issues that they prioritise to their attitudes concerning the economy. We can use survey data to explore these gender differences further.

Different gender, different priorities

Although men and women vote in broadly similar ways overall, they differ in the issues that they prioritise. Evidence (for example, see Rosie Campbell, Birkbeck college) shows that women are more likely than men to prioritise public services, such as the NHS and education. One likely reason for this is that women are, on average, greater users of public services. Women are also more likely to work in the public sector, comprising 66% of the public sector workforce.

Ipsos MORI data shows that, in 2019, 50% of women said that they saw the NHS as the most important issue facing the country, compared with just 35% of men. Women also show a higher concern for education, with 29% viewing ‘education and schools’ as the most important issue facing the country, compared with 17% of men.

The biggest gender difference, however, is on the issue of Brexit. While both men and women listed Brexit as the most important issue facing the country, 69% of men listed Brexit as the biggest issue facing Britain, compared with 52% of women – a gender difference of 17%.

Differences in economic views

As well as differences in the issues they prioritise, women and men differ in their economic attitudes. Generally, research shows that women are slightly more likely than men to prioritise higher public spending – even if this means higher taxes as a result. Women’s prioritisation for higher public spending is evident even among women Conservatives, who are generally more supportive than Conservative men of higher public spending.

Women and men also differ in their perceptions of the economy. Recent research which I undertook (with Rosalind Shorrocks, The University of Manchester) has shown that in the 2015 and 2017 elections women were, on average, more pessimistic than men about the national economy and their household financial situation. This economic and financial pessimism is likely due to the gendered impact of austerity measures since 2010, which have consistently hit women financially harder than men. The research finds, however, that it is younger women who are especially pessimistic in their economic outlook: women under 35 were, on average, nearly 10% more likely than their male counterparts to think that their living costs, their household financial situation, the national economic situation and the NHS had got, or would get, worse over 12 months. Meanwhile, older women were less pessimistic than their younger counterparts, and were generally more similar to men in their economic and financial outlook. However, the data could not be broken down beyond gender and age to include factors such as class and ethnicity, as this resulted in relatively small sample sizes that were too small to draw robust conclusions.

In many ways, this limitation reflects the difficulty in conducting comprehensive intersectional analyses using survey data. This is especially important given what is known about gender (in)equality and how it varies across intersections. For instance, evidence from the Women’s Budget Group shows that BME women were among those hardest hit by the government’s austerity measures.

Women are more likely to select ‘don’t know’ responses

While survey data can tell us a lot about women’s views, there are some further limitations. Women are more likely than men to select ‘don’t know’ responses in surveys. This is one of the most consistent gender differences in survey data.

In the run-up to the 2019 general election, for example, Ipsos MORI data showed that women were over twice as likely to say that they did not know who they would vote for: 19% of women stated that they did not know which party they would support compared to just 7% of men. Such a phenomenon is not new, and the propensity for women to select don’t know responses likely stems from the fact that women have been historically less interested in formal politics than men. However, there is evidence to suggest that this is changing as women participate more in deliberative fora.

Key learning for policymakers:

- Survey data shows that women have specific interests relative to men. Such differences should not be overlooked. In implementing policies, policymakers should ensure that they take a gendered lens in order to adequately address these different interests.

- Policymakers should ensure that they are taking steps to address the economic and financial concerns that women share. This might be particularly important in light of the economic uncertainty surrounding Brexit, and the gendered economic impact that this might have on women following Britain’s departure from the European Union.

- Limitations within survey data mean that they do not always capture women’s voices in their diversity. As a result, policymakers should complement survey data with other methods in order to fill these gaps in knowledge.

Citizen social science: A bridge between evidence, policy and citizens

Liz Richardson

When we think about involving citizens in policymaking, alongside huge potential, there are many challenges. Policymakers may be keen to hear from those who are or may be affected. But they sometimes worry that it might be hard to balance hearing those voices against other forms of expertise, such as scientific evidence. For citizens and those directly affected, they may be confident to offer their direct experience, but some people are all too aware of the limits or partial nature of their experience and want to have a deeper understanding of the wider issues and background. Citizen social science is one approach to address this conundrum.

Citizens as scientists

One way to overcome this divide is for citizens themselves to be part of the evidence data production process and analysis. The idea is to bring together different forms of expertise by directly engaging citizens in the science. Lay people become directly involved in collecting, analysing, interpreting and understanding data, bringing scientific understanding together with their lived experience.

Citizen social science can take place across all or any of the stages of the knowledge production process – from setting the research agenda, to collecting data, to interpreting results and developing policy implications. Citizen social science is gaining ground. There are many examples of citizen science in the natural sciences – like the RSPB’s annual Big Garden Birdwatch survey, and many thousands of examples, such as those on online research platform Zooniverse. Citizen social science extends this people-powered research to other aspects of human life, such as how to address complex policy challenges.

Citizen science for women’s voices

Citizen social science is especially relevant for questions about getting women’s voices into policymaking. It may offer a way to bridge policy, evidence, and citizens in constructive ways which bring those groups and forms of knowledge together. Many examples have suggested that citizen social science, if done in the right way, can be a powerful tool for including groups that are often marginalised, or harder to hear in debates. For example, the work of intellectual activists like Erinma Ochu, and the work of ‘Extreme Citizen Science’ at UCL.

For more information on this topic:

- My own work includes a chapter looking at practical issues of when and how to do citizen social science in the book Evidence-Based Policymaking in the Social Sciences: methods that matter.

- For those interested in more academic debates, I have written in the journal Politics and Governance on how to blend the strengths of participatory research with citizen science.

- There are some great people and resources available online via the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA) including ten principles of citizen science to follow.

To hear women's voices we must consider how, and where, we listen

Eve Holt

There is listening and there is really listening. If you want to ensure women’s experiences are reflected in policymaking, this means not just paying attention to what is said but to how it’s heard. We need to know how to make sure women, in their full diversity, feel included, welcomed, valued, heard, connected, represented and empowered in the process.

The careful and conscious design of any listening exercise, in terms of space, structure and content matters to diversity and to support a positive experience of participation. Over the last five years I’ve made it a personal mission to try and ensure that the diverse voices of women and girls are heard in policymaking in Greater Manchester.

As a founder member of DivaManc (an initiative to grow women’s and girls’ voice, participation and power in the devolved city region), I ran a series of workshops with the Fawcett Society: Making Devolution Work for Women in Greater Manchester.

These led to much learning, summarised by the acronym PIECE - Purpose and Process, Inclusion, Equipment, Conditions and Empathy - all vital to the policy-making jigsaw, but all too often neglected.

Purpose and process

Be transparent

Be clear about the point of the exercise and be transparent with all involved about the policy-making process. Create space to convene, just before the start, to individually set intentions, to share what may get in the way, how ‘listeners’ manage their own state to best listen and what support they need to overcome any potential barriers to participation. Clarify the process: what has come before, how voices will be recorded and used, what follows next and what information and assumptions you are relying on.

Inclusion

Listen to the diversity of women’s voices across the different spaces and networks women occupy

It’s easy to fill rooms with women who would like to inform policy, but that is not enough. Always remember, women and girls make up more than 51% of the population - they are not a minority or a homogenous group. Due to a host of structural barriers, however, women are underrepresented in the rooms and conversations where policy is informed and drafted. And for the full diversity of women’s voices to be heard, we need to recognise and overcome the additional barriers that exist when gender intersects with race, disability, class, age, faith or sexuality.

If organising an event, to listen to women’s voices you need to be intentional about who is invited, the barriers to their participation and what may stop them being heard. Look at the structures, spaces, patterns, mechanisms and models in place ‘below the surface’ to understand where and how women and girls convene, organise, speak and influence, both formally as ‘a sector’ and informally as a web of complex networks. Relationships and trust are important. The ‘Making Devolution Work For Women’ project built up relationships with formal and informal networks and encouraged listening events in women’s centres and community spaces, in addition to more centrally organised events.

Use the event or opportunity to grow connections between a diversity of women, in different positions of formal power, for example in local government between senior leaders and women holding the pen. This will help ensure that voices are not lost or drowned out later in the process and will help build confidence and participation in the process and future engagement.

Equipped

Ensure participants have what they need to participate

Remember the multiple demands that are placed on women makes their time especially precious. Ensure their needs are catered for: provide food and drink, time and space to move around and a conducive and accessible space which is sufficiently warm, light and safe. Access to travel expenses and childcare are essential to enable inclusion of women living in poverty, for example women refugees and asylum seekers.

Having a skilled facilitator supports the psychological needs of participants, creating a sense of welcome and belonging. Use of music, colour and visuals that welcome people on arrival can help democratise a space. Reminding people to leave lanyards, labels and egos at the door and paying attention to names, helps humanise the space and build esteem. Sharing the structure for the session and establishing shared ground rules helps orientate people and provide security and safety.

Where appropriate, equip participants with the data, tools and information to help them to make sense of and contextualise their own expertise and experiences. Ask what they’d find useful as part of the preparation. Providing data, infographics, background information - all provided useful stimulus for purposeful discussion in our workshops.

Conditions

Create conducive and creative space for participation

To help create inclusive, participatory spaces for sharing personal stories and testing solutions, DivaManc workshops used experienced local facilitators who held a space for deep conversation and constructive conflict. Events included a mix of storytelling and techniques such as World Café conversations, Appreciative Inquiry, Open Space Technology, human-centred design and showcasing. Providing space for people to show up in the way they want to is key - space that can breathe and evolve to adapt to the people in the room. Sitting in a large circle of about 50 people at the end of one of our events in 2018, people were invited to offer any reflections from the day. One woman stood up and lifted her bag onto her head before walking around the circle and adding other women’s bags to the load she was carrying. She was practically silent, but her voice was heard by all. Another woman sang. Creative methods such as zines, making banners, cooking and sewing, all open up chances to listen.

Empathy

Listening, connecting and communicating with compassion and empathy

To really listen and to hear the speaker speak their truths requires empathy. The wider the gap between the experiences of the speaker and the listener, the greater the need for all the other pointers above to be given attention and time.

A facilitator helps accelerate this process, designing questions, tasks and space to invite curiosity, compassion and courage into the space and to help break down assumptions by helping participants spot patterns and build shared language, trust and connection.

Pay attention to specific language, words and models used, accepting and extending to unpick and achieve clarity where needed. Acknowledge where there is divergence and convergence in the room. Clean Language and Symbolic Modeling are great tools to support facilitators to tune into and reflect back the words, metaphors and actions of others without ‘dirtying’ with their own language and mental models.

Encourage participants to ask questions of each other to gain clarity and insight. Ensure people have equal airtime.

Reflecting on listening

For women’s voices to be heard equally to those of men, we need women in positions of formal power and structures, spaces, mechanisms and relationships in place to enable women and girls to convene, organise, speak and influence from the bottom up.

The DivaManc campaign set out to help address this in 2016, ‘to put the diva into devolution’ in Greater Manchester, before passing the baton to the GM4Women2028 coalition in 2018-19. Currently GM4Women and the GM Women’s Voice task group are exploring ways to improve connectivity between the formal and informal spaces to amplify the voice of women and girls in policymaking.

To really listen we need to invest in infrastructure and spaces that work for women in all their diversity, where they can participate flexibly, in a way that suits them, both on and offline.

The ideas covered here can be usefully applied to any listening space, regardless of gender, and I hope one day will be seen as normal in policy-making processes.

Getting creative: Giving voice

Sarah Marie Hall

Research is about creativity. We can be creative with our ideas - how we identify and envisage an issue - with the different threads we bring together to create new avenues of thought and investigation.

We can be creative with our design of a research project and its methodologies, including who and where we sample, recruit and enrol. We can be creative with traditional methods, from tweaking to wholesale revamping and even total innovation, in order to gather the types of data to answer our research questions. We can be creative with analysis, developing new means of drawing out key headlines from what our data tells us. Finally, we can be creative in how we share our findings, in terms of the format and audiences, and in the types of conversations and collaborations that might lead to.

Advantages of creative methods

From my own experience of adopting creativity – at various points in various projects, in the framing, designing, delivering and disseminating of my research and activism – I see some distinct advantages to a creative approach.

Firstly, a creative design can help to unpick everyday complexities and draw attention to real-life stories and lived experiences. In some of my own work I’ve used biographical mapping, where participants talk through and annotate on paper their life courses, including the important events and relationships. I’ve also used photo elicitation, where participants have taken photographs of their consumption practices and then talked through their contents on tape, as well as developing co-produced toolkits on how to research particular groups or approach specific political and economic issues. And I’ve used guided tours, from communities to kitchen cupboards, to think about how people navigate and narrate their everyday lives. All of these methods were designed to get at complex issues that might not be easily articulated, but may be represented in more than spoken, more than observed, more than written, forms.

Related to this, creative approaches can offer accessibility beyond the confines of age, education, ability or life experience, including to vulnerable groups (with the right permissions, of course). They can be a tool for empowerment, enlightenment and participation, and can lead to the revising and reassembling of established power hierarchies in research. As a result, creative methods fit well with a feminist agenda.

Creativity can also be invaluable for approaching socially and politically sensitive topics. My own work with families, communities and activist groups (including RECLAIM and Inspire) has explored changing social relations in times of economic turbulence; for example, austerity, devolution and Brexit. I’ve found creative methods to be crucial for allowing open discussion and expression, and to asking difficult questions without needing words.

Creative outputs for stakeholders

Creative methods also lead to creative outputs. A project that uses photo elicitation is already halfway to creating a visual document or an exhibition. But this doesn’t always have to be the case. Some of my own research using traditional interviewing and observations has led to creative outputs – including exhibitions, zines, podcasts and films – by injecting creativity into the dissemination phase, and also drawing on the skills and expertise of others, again a form of collaboration and negotiation of power relations.

This type of creative sharing has, for me at least, always been part of a desire to go beyond hefty reports, complicated language, closed-door events and expensive pay walls.

After all, how can we expect the public and stakeholders to value our research if they never get to see or hear about it?

Co-production: Strategies for being more inclusive

Temidayo Eseonu

The way we develop and deliver policy, our practices and activities, make a big difference to inclusivity. From problem definition, through to formulating and administering policy, processes can either facilitate or serve as barriers to the inclusion of the women’s voices. Co-production (a concept to involve citizens in the design and delivery of public services), is increasingly being applied to policymaking by public sector organisations. Co-production, therefore, presents an opportunity to shape and develop practices for more inclusive representation of women’s voices. However, if there are no active strategies for this, co-production could lead to a lack of representation of women’s perspectives and experiences in policy-making processes.

Inclusive representation

So why is it important to include a diverse range of women’s voices? Because this means a variety of perspectives on a policy problem, that might otherwise have been missed, are heard. This diversity of voices adds value because of unique insights, questions and experiences that cut across the wide range of interests that women have. Ultimately, policy is more likely to be effective when those who are affected by an issue are involved in policymaking to address it.

It would be wrong to assume a category of women with one recognisable set of political interests can be acted upon. Gender intersects with race, disability, sexuality, class, age, religion etc, so it is vital to seek out and include a diverse range of women’s voices for inclusive co-production to be realised.

Principles of inclusion

Borrowing from existing academic literature on political representation, particularly by Jane Mansbridge and Anne Phillips, there are two principles that can be applied to policymaking. Ensuring that diverse women are present in co-production is the first step in ensuring that they can bring their perspectives to the nature of the issues and the potential solutions. However, women taking part in co-production does not, on its own, guarantee that issues women care about are considered. Co-production processes should encourage women to speak for women; to speak about their experiences as women. Where there is a diverse range of women involved, they can represent and speak from the perspective of a wider cross section of the female population. Inclusive co-production then brings a social group’s perspective into policymaking.

But achieving inclusive co-production will not just happen without active strategies.

These active strategies can include:

- Understanding the population you wish to work with and going to where they are

- Framing the issue and how you want them to get involved, in a way that matters to women

- Where there is no existing relationship with particular groups of women, working with community groups (formal and informal), prioritising those who will facilitate access to women’s voices

- Making co-production activities more accessible and welcoming, so that women feel able to contribute, considering the language used, both to attract participants and during the events

- Depending on the population you wish to work with, considering accessibility needs, (for example provision of childcare; location and time of events; the covering of travel expenses; and, where possible, compensation for people’s time)

Case study

Young women speak out

Reclaim

In order to reach young women from working-class backgrounds, RECLAIM staff installed themselves into working-class areas and targeted schools with below average performance. They targeted schools and youth clubs in the most deprived areas of the UK, which are mainly populated by working-class young people. Here, a young participant talks about the process:

How was RECLAIM able to reach you as a young woman?

RECLAIM had presented themselves in my school assemblies and showed pupils how and why young, working-class people should be involved in politics and lead change. Two of my close friends got involved with RECLAIM as a result of these assemblies and I decided to join too. All RECLAIM staff are working class or from working-class backgrounds, and so they are able to empathise with young people and connect with them on a deeper level when talking about the hardships and barriers faced by young people like us, as they were once in the same position. Due to the mutual understanding and connection they have with working-class young people, they come across as genuine, authentic and trustworthy when presenting the charity and their educational programmes. This interests and inspires young people to participate and engage in RECLAIM projects.

What message do you have for policymakers who wish to engage with young women?

Policymakers wishing to engage with young women need to be genuine and transparent with the young women they are looking to engage. For example, they should clearly explain the purpose of the engagement, as well as the roles young women will play and the outcomes of their engagement. Policymakers should also understand that simply engaging with a specific group of ‘young women’ does not cover the vast demographic, issues, ideas and contributions of the rest (ie only engaging with white, middle- class young women, who are most likely to be engaged in politics and leading change, will not be representative of all young women’s views). Therefore, policymakers should aim to mainly target young women from marginalised backgrounds, for example working class, BAME, LGBTQ+, as only then will real change occur.

Case study

Chai and Chat

Atiha Chaudry

Traditional methods of community engagement have led to community consultation fatigue,

disengagement, apathy and cynicism.

BME communities feel their experiences are undervalued and engagement with them is just a tick-box exercise rather than genuine co-production.

Chai and Chat is a community engagement approach developed by MBMEN through years of experience in engaging with diverse communities on a range of topics and particularly those that can involve complex, difficult and sensitive issues.

Why Chai and Chat?

It is about engaging BME women and girls in a safe environment so that they are encouraged and feel they can contribute and add value to policymaking. The Chai and Chat approach is about creating informal spaces for discussion on specific issues. It is centred around a community cultural connector leading small group discussions as people eat and drink.

This approach means:

- BME communities are involved with the planning and choice of topics for engagement through community cultural connectors who are trusted people and sources within the communities. We use community cultural connectors as they have better reach than outsiders because of their understanding of their communities and because they are trusted by them.

- The BME communities participating understand the purpose of co-production activities and can actively contribute because policy and government language are made relevant.

We utilised our Chai and Chat approach in a recent commission by the RadEqual Network in Manchester focusing on the 'Prevent', 'terrorism' and 'hate' agendas. We were asked to engage with BME women and girls (primarily but not exclusively) to build awareness, learning and confidence so that they can better address the consequences of this type of hatred in society. To make it accessible, we branded the commission 'Love Our City'.

We were able to reach BME women and girls whose voices would ordinarily be less heard. As this is an issue that matters to BME communities with social and personal outcomes, the provision of safe community spaces to share their views, perspectives and thoughts was welcomed. It was important to have an informal, loosely-structured and flexible discussion as part of creating a space for women to contribute to the discussion.

Most importantly, it is not just enough to include women’s voices; their perspectives must influence policy decisions. This involves the sharing of power between policymakers and women in order to avoid the distrust and disengagement that could arise from meaningless co-production.

Case study

'Becoming visible': Inspiring women to speak out in Oldham

Sally Bonnie

Sally Bonnie, founder of Inspire Women Oldham tells us what sharing of power could look like from her experience of being on the receiving end of initiatives that sought to include women's voices.

Inspire Women Oldham is a diverse, multicultural community of women who nurture women to re-connect and re-imagine their lives, promoting civic engagement and embracing and celebrating new power values. I started Inspire Women Oldham because I was tired of describing women and young women by the multitude of labels they carried around like shackles, keeping them stuck and disempowered. I believe a vital issue for society today is how to make the voices and choices of women, young women and girls all count for something.

From the outset, Inspire has been about collective participation, de-emphasising the role of traditional hierarchies. How we operate is important because it sends out a clear message that says “you can connect here, you can contribute here, you can learn here, you can re-discover the gifts, the assets you left behind when you began to see yourself only as a set of labels defined by others”.

Expectations and regaining control

Expectations about participation increase as women begin taking control over their lives and recognising the value of their input in enabling others. Women become confident in sharing their skills and reaching out to women who, just like them, have known the negative impacts of poor health, isolation and loneliness. This approach has seen so many women create new lives for themselves.

In comparison to the authentic space we have created at Inspire, many external interactions with policymaking are in the forms of systems based on old power structures. Even when you are invited in to ‘co-produce’ or ‘contribute’, ‘old power’ watches over the proceedings. The best description I ever heard of this scenario was: “It’s like being invited to a party and then being told what to do.” So much needs to change here in terms of relocation of power, along with sustainable investment in individuals and communities.

Participation and power

Inspire favours approaches that embrace power with, rather than power over. Participants act to improve their own conditions, surrounded by like-minded women. They try things out, co-create activity, share ideas and compassion. Power is not top down; everyone is welcome here to contribute; power is sideways woman to woman. Participatory and equitable approaches have enabled many women to discover that wisdom and wealth resides in them, that they can invent solutions, their creativity and innovation showing that a different approach to power is possible.

That’s why these approaches matter so much in the learning journey of those seeking new models of power. Women discovering their voices, women becoming visible, women changing because they are being seen and heard is what drives me fiercely.

A seat at the table: Getting women's voices into decision making through citizens' assemblies

Leah Culhane and Rebecca McKee

Citizens’ assemblies are becoming an increasingly popular way to engage citizens in policymaking and inform decision makers on public opinion. But how and why might they be used to include women’s voices?

Existing patterns of gender inequality mean that policies affect women and men in quite distinct ways, yet political institutions continue to be dominated by men. The recent UK general election returned a record number of 220 women, but this only accounts for 34% of MPs. At the local level we see a similar pattern: following the 2019 local elections, approximately 36% of local councillors in England and 26% of councillors in Northern Ireland were women (House of Commons briefing, Women in Parliament and Government). Following the 2017 local elections, the percentage of women councillors was 29% in Scotland and 28% in Wales.

Devolution in regions across the UK offered opportunities for change with significant decision-making powers transferred to combined authorities and metro mayors. However, so far it has done little to challenge gendered patterns of underrepresentation. Of the 95 members of combined authority boards, just 21% are women and all of the eight metro mayors are men.

The reasons for women’s underrepresentation within politics are well documented. Political parties are less likely to select women candidates because they feel they are less electable or because they do not fit the traditional mould of an ideal leader. Political parties are also organised in such a way that a number of personal resources are needed to actively participate including money, time, flexibility and party connections. Men continue to have greater access to these resources due to the unequal division of domestic labour, the gender pay gap, and the gendered barriers to participation.

Why use citizens’ assemblies to include women’s voices?

Without equal numbers of women at the top table of decision makers, citizens’ assemblies offer an opportunity to feed women’s voices into conversations about the decisions that affect their lives. The core purpose of a citizens’ assembly is to give decision makers access to the informed and considered views of the public. Assembly membership is designed to be broadly representative of the population, giving everyone an equal chance to participate. Members are usually chosen using stratified random sampling. The composition of the membership is stratified by demographic characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, region, age and social class. Attitudinal criteria can also be included, depending on what the assembly is deliberating. For the Citizens’ Assembly on Brexit, membership was stratified on the referendum vote to ensure participants broadly reflected the way the UK voted in the EU referendum and for the Citizens’ Assembly on Social Care, stratification included attitudes towards taxation for public spending.

Gender-balanced citizens’ assemblies cannot be considered a substitute for women’s political representation. Much more needs to be done to ensure that women are present within national, local and devolved bodies. But, given the current deficit of women, it is vital that other mechanisms are used to ensure that the voices of women are being fed into policy-making processes. Citizens’ assemblies, if run correctly, are a great way to include women’s voices and to highlight women’s issues in public debates.

Citizens’ assemblies can also be used to inform decision makers on specifically gendered issues. Ireland’s Convention on the Constitution (2012-2014) asked citizens to deliberate on the role of the women in the home, women’s participation in politics and same-sex marriage; while Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly (2016-2018) asked citizens to deliberate on the question of abortion. In January 2020, Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on gender equality will be dedicated entirely to gender-related issues with citizens deliberating on the gender pay gap, unequal care responsibilities and barriers to women’s leadership.

Citizens’ assemblies often have no legislative powers, however, they can provide legitimacy for politicians to propose legislative change. The two assemblies that have already taken place in Ireland opened up the political space, encouraging the Irish government to call referendums on legalising same-sex marriage and repealing the eighth amendment (the clause in the Irish constitution which prohibited abortion), both of which were passed.

How do we ensure citizens’ assemblies hear women’s voices?

Getting women in the room will not, on its own, ensure that women’s and men’s voices will be heard on equal terms. Gendered power dynamics can still be present within deliberative spaces which can impact on whether women feel able to speak up and whether their voices will be valued by other participants when they do. In order to combat this, seating plans must be designed to ensure gender balance at each table and professional facilitators are necessary to ensure that all people are able to participate and have their voices heard.

Data gathered at the Citizens’ Assembly on Brexit looked at whether there was variation in the amount of time participants spoke during the deliberation. While there were some differences amongst individuals, there was no statistically significant variation across any of the demographic or attitudinal criteria. So, men were not more likely to speak more than women. However, good planning and design is necessary to ensure that this is the case.

In order to recruit a representative sample, citizens’ assemblies must also combat structural societal issues that act as barriers, preventing some people from attending. This includes providing compensation or incentives, such as a ‘gift of thanks’ (around £150-£200 per weekend), covering travel expenses and providing accommodation. Ensuring that financial support is in place is key to ensuring that traditional barriers to participation are minimised.

Care provision is also of vital importance to ensure women can participate. Assembly organisers should look to cover the costs of participants requiring a carer including their travel, accommodation and all associated costs. They should also cover some childcare or respite costs. Venues and materials need to be accessible to all, and the cost of additional adjustments such as a British Sign Language interpreter, should be covered by organisers.

A key aspect of a citizens’ assembly is providing fair and balanced information to the participants. In addition, organisers must also ensure that women are represented among those invited to speak and give evidence to the assembly.

Key messages for policymakers

- Citizens’ assemblies and other forms of deliberative democracy have the potential to ensure women’s voices are included in decision-making processes.

- This doesn’t happen by accident - good design, funding, planning and an explicit consideration of gender are essential in order to ensure that barriers to participation are addressed and a diverse range of women are heard.

- To be successful, organisers must ensure: a robust recruitment method; a representative membership; accessibility; incentives to attend; professional facilitation at tables; and a range of evidence givers.

Case study

Bristol women's commission and Bristol women's voice

Penny Gane

We set up Bristol Women’s Voice (BWV) following our research (commissioned by Bristol City Council) into whether women in Bristol felt they had a voice with decision makers. We got a resounding ‘no’ from hundreds of women we spoke to around the city. BWV was set up with clear priorities identified in the research, including employment, caring responsibilities, health and women’s and girls’ safety.

BWV became a charity two years ago. We have moved in seven years, from a tiny organisation with one part-time coordinator in a shared office to a very small charity with 10 part-time staff, including a new director and our own office. BWV is a network for all women in the city. BWV works with women in communities, women’s organisations in the city and citywide partnerships.

Our activity is very varied. BWV does community-based project work (currently health inequalities and maternity rights), runs a volunteering programme, a zero-tolerance initiative (of violence against women and girls), a City Listening project, and a huge International Women’s Day celebration in City Hall, attended by around three thousand women every year. BWV also runs women’s hustings at elections of MPs, elected mayor, Police and Crime Commissioner and West of England Combined Authority elected mayor.

Bristol Women’s Commission

Bristol Women’s Voice set up Bristol Women’s Commission when our elected mayor signed the European Charter of Equality of Women and Men in Local Life on International Women’s Day in 2014.

The Commission is made up of senior women leaders from key organisations in the city: University of West of England, University of Bristol, West of England Combined Authority, Avon and Somerset Police, University Hospital Bristol, Clinical Commissioning Group, Trades Union Congress, City of Bristol College, Bristol schools, First Bus, Trinity Mirror, The Fawcett Society, Voscur, One City Plan, four councillors from different parties as well as women Cabinet members, and our task group chairs.

A lot of the work takes place in our six task groups: Women’s Safety, Health, Representation, Women and Girls’ Education, Women in Business, Women and the Economy. The task groups are made up of academics, stakeholders and experts in the field.

The difference we’ve made

Bristol Women’s Voice is a powerful voice for women in the city with thousands of members and thousands more who take part in our activities. It is an ongoing engagement and consultation mechanism that works both ways. It empowers women. It has a route to decision makers.

Bristol Women’s Commission has huge reach through all the key organisations in the city - public, private and voluntary sector.

We have had many successes which go beyond policy change:

- The Commission ran a 50-50 campaign working with political parties to stand women in safe seats, training women in entering public life and setting up a cross-party group of women councillors to support new women councillors. The percentage of women councillors increased from 28% to 43% in two years.

- It also set up a Zero Tolerance Programme to get employers to recognise and tackle gender-based violence, abuse, harassment and exploitation. BWV managed the initiative.

- Our Education Task Group has established an annual citywide programme of girls’ conferences, bringing girls from different communities together to be empowered and inspired.

- Our Enterprise Zone aims to become a beacon of gender equality. Already developers are providing language and business language classes with free crèches and our MP is campaigning for the station to be made accessible.

- Our Business Task Group has launched a Women’s Charter for Business, with more than thirty signatories from major companies in the area committing to a number of initiatives which get more women into leadership roles and ensure a female-friendly workplace.

- The Commission ran a spectacular programme of centenary events raising the profile of women and women’s organisations throughout the city. It also has a strong scrutiny role. Strategy leads are invited to present to us on what they are doing for women in various roles, including Industrial strategy, Inclusive Growth strategy, Local Economic Plan and One City Plan.

- The Commission has legitimacy from local government, the European Charter (of which we are the only UK signatory) and our elected mayor while maintaining some independence from formal local politics.

- BWV has an established approach to encouraging the engagement of women who traditionally don’t engage, for example: a Lantern Parade, International Women’s Day, Women of Lawrence Hill and now our City Listening Project.

- The Commission works through established leadership structures and multiagency task groups. It develops policy and strategy.

Policy changes

- We have a new chapter on women’s health in the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. We have a new Women’s Health strategy.

- Misogyny is now recognised as hate crime by Avon and Somerset Police.

- Universal Childcare and Period Poverty are two of three priorities for One City Plan.

- We have developed best practice menopause policies in the workplace.

- We have a Women’s Charter for Business.

- Zero tolerance pledges from local and regional employers incorporate new policies and actions to tackle gender-based violence, abuse, harassment and exploitation.

- The Zero Tolerance Programme supported a local woman to campaign to enable women in refuges to vote, resulting in national law change. City Listening Project (reaching women whose voices are not generally heard) will feed back to the Government Equalities Office to influence national policy.

- We are currently contributing to local sustainable development goal five.

- We are about to undertake an analysis of Health Improvement Teams by sex.

A reflection

What we do is a mix of policy change and activism. We look for solutions and develop strategies and action plans to bring about change. A women’s commission has proved to be an excellent vehicle for getting women’s voices into policymaking. Our women’s network feeds into the Commission and manages projects on its behalf. The overarching One City Plan is changing the make-up of its boards to include our Commission members and to ensure our strategies are embedded in citywide policy.

We look forward to delivering more for gender equality in our city in the years to come.

The Women's Budget Group: Campaigning for a gender-equal economy

Jenna Norman

For over 30 years the Women’s Budget Group has analysed the impact of economic policy on women and men and promoted alternatives for a more gender-equal future. As an independent network of academic researchers, policy experts and campaigners, we try to bring feminism to economics and economics to feminism.

The economy and gender

What we’ve shown, year on year, is that economic policy impacts differently on women compared with men and on different groups of women and men because they continue to be differently situated in the economy. Most importantly this is because, as many of us know all too well, women take on responsibility for the majority of unpaid care work which leaves them with less time to do paid work and leisure activities. This means that, on average, women earn less, own less and contribute less to their pensions over the course of a lifetime.

As a result of these inequalities, tax policy and public spending also have a different impact on women. Women tend to lose out more from social security and public service cuts as they’re more likely to rely on them to take up care and, for a larger part of their income. Tax cuts also tend to benefit men more than women.

Women make up 69% of low earners in society, so increases to the personal tax allowance since 2010 have mostly benefited men over women. The impact of fuel tax changes is similarly gendered: women are less likely to drive long distances so freezing the fuel duty saves more money for men than for women. Taken together, tax cuts have cost the Treasury £46 billion since 2010, eroding the base to pay for social security and public services. And it’s not just about the money. The design of policy can have negative impacts on women. Take Universal Credit – not only has its value been cut by freezes to working age benefits, but it is also dangerous in design because it is paid into a single bank account monthly which can actually increase women’s economic dependence on men and therefore exacerbate the risk of abuse (see the Women’s Budget Group’s policy briefings and reports online for more information).

Other inequalities

Inequalities based on gender intersect with other structures of inequality including race, class and disability, which means that policies don’t just impact differently on women and men, but on BAME women differently from white women. For example, Women’s Budget Group research with the Runnymede Trust into Universal Credit showed that BAME women claiming Universal Credit would be £5,000 a year worse off than if they were claiming under the old system, whether or not they were in work. This is because women of colour also face racial discrimination in the labour market and society which means they are statistically more likely be economically disadvantaged.

When it comes to social security, disabled women have been multiply deprived by cuts; migrant women without recourse to public funds are even more impoverished; and the two-child limit, contained in Universal Credit, is directly discriminatory of BAME families who are statistically more likely to have more than three children.

Economic policy which misses these key impacts is at best ineffective and at worst, exploitative. It can reproduce gendered norms about what it means to be a woman or a man in the economy or ignore them all together. For example, efforts to enrol women into executive roles are laudable but without consideration of childcare, parental leave and public services, they simply leave women with double the burden.

Legal obligations and duties

We at the Women’s Budget Group have been assessing economic policy in this way for years and the government is supposed to too: the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) contained in the Equalities Act 2010 legally obliges all public bodies to have ‘due regard’ for the impact of their work on equality. For most public bodies this means doing Equality Impact Assessments (EIAs) which assess policy to ensure it does no harm and instead, promotes equality. For EIAs to be more than box-ticking exercises they must consult civil society, be renewed regularly and always take the intersectional approach outlined above.

A meaningful EIA should take account of unpaid care, assess the impact on distribution of resources for both households and individuals, consider a cumulative approach working across departments, and consider the impact of policy both immediately and over the course of a lifetime.

A new economic settlement

These are just a few examples of how discrimination continues to be baked into economic policy. You can find more about gender budgeting and EIAs in the Women’s Budget Group’s casebook Women Count and our EIA policy briefing, both available from our website.

But it’s not enough to analyse, advise and critique, we can and must do things differently. Our Commission for a Gender-Equal Economy hopes to come up with a new economic settlement which provides for all women, regardless of background or circumstances to ensure the economy works for everyone.

Case study

Women's and girls' equality: Greater Manchester's journey so far

Amy Foots

Greater Manchester has been on a journey, from early conversations and aspirations to ‘turbo charge’ women’s equality in the city region to where we are now, on the cusp of establishing a Greater Manchester Women and Girls’ Equality Panel. Our aim is to accelerate gender parity and ensure the voices of women and girls are taken into account in policy development and delivery, across the public, private and voluntary sectors.

Through the drive and passion of some of Greater Manchester’s female leaders, the issue of women’s and girls’ equality is now firmly on the Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s (GMCA) agenda. At their meeting in March 2019, the GMCA agreed to establish a cross-agency working group to develop our shared understanding of the issue of gender inequality, and to develop a joint work programme capturing actions that would embed the voices of women and girls, and change current practices enabling all women and girls to achieve their potential and not be disadvantaged due to their gender.

Shared evidence, interests and an action plan

The working group, known as the Women’s Voice Task and Finish Group, chaired by the GMCA’s Portfolio Lead for Equalities, has brought together a membership of academics, lobbyists, local government leaders, business representatives and a range of local authority officers and people working in this field. It has led the development of a shared evidence base and a broad work plan, which focuses on the activities required to utilise and embed the developed evidence base; shape public service practice to embed equalities assessments; and outlines the proposed actions to be delivered in order to achieve the overall ambition of establishing Greater Manchester Women and Girls Equality Panel which will be overseen by the GMCA and be firmly embedded within GMCA governance.

The work undertaken by the Task and Finish Group has set a strong foundation from which Greater Manchester can develop a Panel to embed women and girls’ equality within the infrastructure of GMCA and systemise the voices of women and girls’ in policy development and delivery. The issues are now clearly evidenced and immediate priorities have been identified; the trick now is to establish a mechanism to ensure the evidence, passion and enthusiasm to drive change is not lost in the system, and instead shapes and directs the system to change.

Prioritising themes and issues

The initial focus of the Panel will be to develop a detailed work programme, prioritising issues based on the evidenced need, and identifying headline targets and outcomes to be achieved. It will operate in a way that links with a convened officer working group and also directly to grassroots organisations and women’s and girls’ representatives.

The work undertaken to date by the Task and Finish Group has identified priority themes to focus the activities of the Panel, which will be developed into the work programme and explored in detail. These are:

Representation in public life

A focus on women’s representation and support for childcare and parental leave. In addition, a focus on women’s and girls’ participation in politics will also form part of work in this area.

Safety

Activity under this priority will look to make advancements in informing best practice around violence against women and girls (including trafficking and anti-slavery) and will look to identify other key areas of focus around women’s and girls’ safety in Greater Manchester.

Employment, business and the economy

Activity under this priority will involve the formation of best practice recommendations for focus areas such as:

- working with the Greater Manchester Good Employment Charter, to improve secure and well-paid work

- women’s employment and progression to managerial/board level positions

- women’s participation in the STEM sector (science, technology, engineering and mathematics)

- education: school readiness, attainment, aspirations

- skills: access to apprenticeships and employment for women and girls

- support for female entrepreneurs

Health

Activity under this priority will look to recommend specific focus areas of best practice to work into the Panel. For example, the Bristol Commission’s Health Conference 2017 highlighted focus areas to develop, such as alcohol support, domestic violence, healthy lifestyles and the importance of integrated approaches to women’s health.

A commitment to change

To ensure strategic fit with the established GMCA infrastructure, in reviewing priorities, the Panel will work with the existing GMCA portfolio structures, building on the expertise, policies and strategies in place, and key personnel who are responsible for their delivery. Ensuring the Panel has a direct link into the GMCA will be key to its future success.

It is still early days for this work, but the efforts to date demonstrate a willingness and a commitment to system change which will bring about real differences to the lives of women and girls in Greater Manchester and beyond.

Afterword

Donna Hall CBE

It’s my great pleasure and honour to write this afterword to such an important publication, looking at how we put gender equality into policy, in Greater Manchester and beyond.

We are incredibly lucky to have a Mayor, Andy Burnham and our Deputy Mayor, Baroness Beverley Hughes who are both passionate feminists and equally passionate about equality of opportunity for everyone who lives or works here. We are equally blessed to have so many unelected ‘spark plug’ leaders who advocate and campaign for gender equality in their daily lives, working in academia, social enterprises, the health care sector, community and voluntary organisations.

Greater Manchester has been the trailblazer for so much new and innovative policy development. However, many of us recall the unfortunate press photograph of ten white men signing the devolution agreement which attracted negative publicity for such a lack of diversity. Yet much of the drafting of the policy documents that were the basis of the negotiations with government were drafted by very clever, hardworking, tenacious and determined young women; women who wanted to see a better future under a devolved system, bringing resources and control closer to our local communities and away from Whitehall.

This exciting compilation of ideas and information has been put together by passionate women who want to see this ongoing patriarchal situation change. It explores what actions combined authorities with devolved powers and others involved in policymaking can take, to give women a seat at the table and a louder voice.